秋田県大館市山田地区に四百年伝わる「山田獅子踊り」。その伝承を通して、地域に潜在する世代間や文化的背景の違いを可視化し、地方における「継承」という行為の意味を再考する試みとして本プロジェクトは構成されている。

かつて作物の豊穣や健康を祈るために行われてきたこの踊りは、時代の変化とともに担い手の減少や価値観の揺らぎの中で2007年に一度途絶えた。翌年、子ども会や帰省した若者たちの協力によって再び復活を果たしたものの、継承の難しさは今も地域に根深く残っている。女性の参加が禁じられてきた慣習や少子化、高齢化など、社会的な要因が複雑に絡み合う。これは山田地区に限らず、世界中のローカルコミュニティが抱える共通の課題でもある。

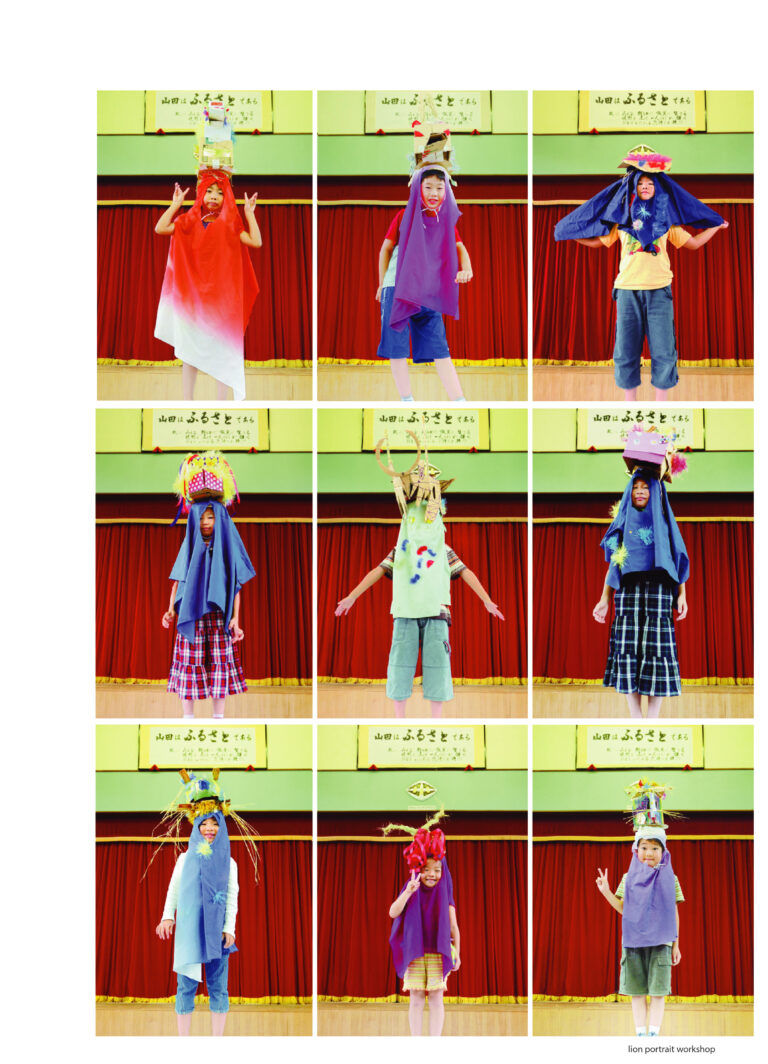

プロジェクトでは、長年踊りを継いできた二名の高齢者への聞き取りを通じて、その背景にある価値観や時代の変遷を探った。その上で、これまで踊りに参加する機会を持てなかった地元の子どもたちを対象に、彼ら自身の解釈による「獅子頭」を制作・装着するワークショップを実施した。伝統を“教える”のではなく、“体験を通じて触れる”ことで、継承の在り方を身体的に捉え直す試みである。

展示は、短編ドキュメンタリー映像、ポートレイト写真、そして地元酒造の酒箱を素材とした鑑賞ブースによって構成される。これらの要素は、かつての祭りを再現するのではなく、現代の視点から伝統と社会の関係を問い直すための装置として機能している。来場者は空間の中で、地域の人々が抱える継承のリアリティに直面し、そこから新しい対話が生まれる。

作者自身もまた、石川県白山市鶴来地区で「獅子舞」に参加してきた経験を持つ。地域合併や担い手不足といった似た課題を抱える現場に立ち会ってきたことから、「山田獅子踊り」への関心と、伝統文化をどう受け継ぎ、変化させていくのかという問いが生まれた。

本プロジェクトは、伝統を保存することそのものよりも、「伝承するとはどういう行為か」という根本的な問いを通じて、地方文化の可能性を探る実践である。本プロジェクトは、同地域でしばしば重く語られがちな「伝承」というテーマを、世代間に横たわる価値観のズレや社会的な断層を手がかりに、軽やかに見つめ直そうとするものである。多様なアートの手法を通して、景勝を”保存”ではなく”対話”として捉え直す姿勢がその核にある。

In the Yamada district of Ōdate City, Akita Prefecture, a traditional performance known as Yamada Shishi-odori (the Yamada Lion Dance) has been passed down for over four centuries.

Through this inherited ritual, the project seeks to visualise the cultural and generational differences embedded within a rural community, and to reconsider the meaning of transmission in the context of contemporary regional life.

Originally performed as a prayer for abundant harvests and good health, the dance once ceased in 2007 as local practitioners dwindled and values shifted with the times. It was miraculously revived the following year by local children and young people returning home for the summer, yet the challenges of continuation remain deeply rooted.

Customs that prohibited female participation, declining birth rates, and an ageing population intertwine with broader social changes — issues not unique to Yamada, but shared by many local communities across Japan and beyond.

The project emerged through interviews with two elderly bearers of the dance tradition, whose stories revealed the shifting meanings of faith, continuity, and belonging. Building on these encounters, workshops were held with local children — including girls who had previously been excluded — to create and wear their own interpretations of the lion’s head. Rather than reproducing the dance itself, this became an embodied experience through which the act of inheritance could be reconsidered.

The exhibition comprises a short documentary film, photographic portraits, and a viewing booth constructed from sake crates donated by a local brewery. Together, these elements form an installation that does not seek to recreate the festival, but to re-examine the relationship between tradition and society through a contemporary lens.

Visitors are invited to engage in conversation — with each other and with the layered memories of the place — encountering the realities and contradictions of cultural transmission today.

The artist himself has long participated in the Shishimai (Lion Dance) of Tsurugi in Hakusan, Ishikawa Prefecture, where similar challenges of depopulation and municipal merger have transformed community life.

The project’s starting point lies in this parallel experience — an awareness of shared fragility and a desire to question how traditions can be inherited, reinterpreted, and sustained.

Ultimately, TRADPOP does not aim to preserve tradition as static heritage, but to ask what it truly means to “pass something on” — a reflection on continuity, transformation, and the cultural potential of local practice in the present day.

The TRADPOP project re-examines the often weighty discourse surrounding cultural transmission by focusing on the subtle dissonances and social shifts that arise between generations.

Through a range of artistic strategies, it proposes inheritance not as an act of preservation, but as a form of dialogue — a process of reinterpretation rather than repetition.